Sweden was where our family story began and, in some ways, where it ends.

So does Painful Joy.

Welcome to this special section on Painful Joy and Sweden.

A bit of background:

When I was young, my mother would always tell me that my hair was blond because I was born in Sweden. I believed her in those early years, though wondered what the story was about my brown eyes, especially when my parents and sister all had blue eyes? I'll leave that for readers to ponder. Suffice it to say that our relationship with Sweden was a very special one.

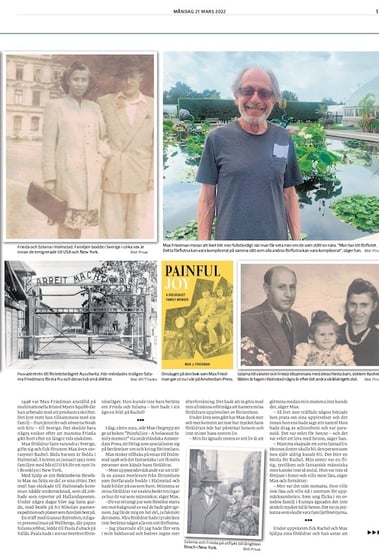

As you will learn in Painful Joy, my parents met there -- in an aliens' camp after their liberation from Bergen-Belsen and, as you probably also know by now, for a long time, I didn't know, nor did I want to know much more. What I experienced every day with our less than normal life was enough. Yet, in April 1998, really for the first time in my life, I decided it was time to know what that Swedish birth certificate I kept in a safety deposit box, was all about. So I sent an email to City Hall, Halmstad, Sweden, and asked for any information anyone there I had about my past and that of my family, providing the bare details of their surviving, meeting and marrying somewhere in Sweden (it turned out not to be in Halmstad after all, their names, and my birthdate and that of my sister. I also sent along a photo of my birth certificate. A response soon came back from a reporter named Tony Balogh, who covered the local municipal beat and suggested that if I were to visit Halmstad and allow him to write a story about that, visit, he would guide us around the town and try to find out more about our past. So in late May 1998, our little family, Jennifer, my wife, and Eric and Noah, our sons, embarked on a journey of a lifetime. It was just a few weeks my mother died at age 88 and five years after my father passed away. But it was time to know at least something more. The result was an extraordinary experience detailed in the article you see below,. Underneath I've provided a translation. And you can learn more in Painful Joy, which starts with my father writing a letter for help to a lawyer in Stockholm shortly after he meets my mother -- and it ends with our journey back in time -- once my parents are gone -- bookends to their lives and our life with them. The book begins where they began with each other, then looks back at their lives and losses before they met. It then takes the reader on a journey as we leave Sweden and come to the U.S., to begin to understand the nature of survival in its complicated and unending dimensions.

This 1998 trip to Sweden, in a sense, begins the journey. Below is a translation of the coverage of that journey by a reporter for the Hallandsposten, the local Halmstad newspaper where my parents lived after they were married and where my sister and I were born.

Hallandsposten, May 23, 1998

He Found His Roots in Halmstad; Max Friedman on a Whirlwind Visit to his Former Hometown by Tony Balogh

On the 15th January 1952 Szlama and Frida Fridman, two Polish citizens, alongside with their children Rachel and Max, embarked on the SS Gripsholm, a passenger ship belonging to Svensk Amerika Linien, with a destination: New York. They left behind them almost seven years of their lives in a country that towards the end and after the end of the Second World War gave a new home to some of those thousands of survivors from Nazi concentration camps. On their way they changed their surname three times: from Frydman via Fridman to the American sounding Friedman.

Says Max upon returning to Halmstad for the first time in 46 years: "When we left for the U.S. I was barely two years old. During my upbringing I would constantly hear my mother tell stories from and about Sweden and Halmstad, how kind and helpful everybody was towards her and her family. This trip has taken a special meaning to me. My father died five years ago, my mother died in early May. She had been sick for a long time. I don't have any relatives alive that can tell me about our time in Halmstad." Max's only physical connection to Halmstad is his birth certificate, but with the help of this and some old records at the parish of St. Nikolai, a partly new world opens up.

Glass in Soup

Max parents, Frida and Szlama, were born shortly before the outbreak of the First World War in Krakow and Zarnowice respectively. They both got married before the start of the Second World War and they both lost their families in the Holocaust, in Max's father's case, his wife and their two children. Max recalls how his mother constantly spoke about her experiences in the camps while his dad chose silence. Says Max: "After the war my father oddly enough seemed to be a happy person content with this life. My mother on the other hand remained a rather gloomy person for the rest of her life. Her experiences had a strong impact on her. She used to recall three or four different stories. One contained memories towards the end of the war when the Germans did absolutely everything in their power to eliminate the prisoners of the camps. No evidence was to be found. "The Germans used to put glass in the soup that was given to the prisoners. My mother refused to eat it. She told us how her dead mother used to come to her in her dreams and 'feed' her. When the day arrived, she wasn't hungry anymore and she never had to eat the soup. This went on for several days. Maybe that's how she survived."

The children

After the war Frida and Szlama became very protective about their children, bordering on overprotection. "When we came to New York, we settled in a part of the city called Brooklyn. We lived in a tiny apartment close to the Atlantic Ocean and near the amusement park in Coney Island. Neither my sister nor I were allowed to go bathing in the ocean, the explanation being the risk of drowning. We weren't even allowed to go on the rollercoaster," explains Max. He laughs. "But at the same time, and this is so strange, they encouraged me when I wanted to go to Europe in the 60's. 'You go, it´s probably for the benefit of your education.'"

Almost 30 years later Max works for the American medical firm Bristol-Myers Squibb with all sorts of writing in a public relations capacity. His wife Jennifer is a librarian and their two sons Noah and Eric attend Yale University. The family resides in a small community in a suburb situated to the north of New York.

Did your father ever break his silence?

"Oh yes. In 1968 [actually 1970], [there was a possibility that I would be drafted for military service in the Vietnam War. My parents would probably never cope with the fact of maybe losing someone dear again in a war. Their lives would be shattered. I told this to the appropriate authorities and they asked me to do an "interview" with my Dad and send a copy to them," explains Max who subsequently never had to go.

"When my father was separated from his wife and their children he kept her sweater. He carried it with him all the time, hoping they were going to be re-united one day. He never found out exactly what had happened until someone told him the facts. That person had seen his wife and children on their way to the gas chambers. At that moment he dropped the sweater. [I think] my father worked as a cook. That's how he survived, he smuggled food to the rest of the prisoners."

Roots at Wallbergs

Max's birth certificate reveals information in a land register. Two addresses appear: one the corner of Brogatan-Skeppargatan and another at Furuvägen 24. Szlama's occupation was said to be "textile worker." Is there a possibility that he might have worked at either Nordiska Filt or Wallbergs?

Yes indeed, Gunnar Björnfors, a former staff manager at Wallbergs from 1946-91, confirms this piece of information. We all meet him ona Sunday when the sun is high up in the sky and a gentle breeze flows through the air. Gunnar is well known for his excellent memory. On behalf of Max and Hallandsposten, he made a big dive into the archives of Wallbergs. He recalls how Frida and Szlama probably arrived to a hospital in Malmö and that they were transferred to Halmstad in late 1945 or early 1946. They were given housing at Frennarpsgården.

The church records show that the Fridmans moved to an apartment at the corner of Brogatan-Skeppargatan on October 9th 1946. They got married at the Jewish parish in Malmö on the 25th of December. "I sometimes don't understand what they saw in each other,"[Max says.] "They were totally mismatched and were each other's opposites. Maybe it had something to do with the fact that my father's name was Fridman; that was also the name of my mother's first husband."

Several things happened during the next year: Frida stopped working at Wallbergs on July 5th. Twelve days later she gave birth to Rachel. And on the 17th the family moved to Furuvägen 24. That house was closer to the place where Szlama worked at the time: the Francke Shoe Factory on Nässjögatan. Szlama soon got work at Wallbergs.

The open arms of Paula

Gunnar Björnfors has vivid memories of the 15-20 or so Jews who were employed at Wallbergs. The company at that time employed some 800 workers. "I left school in May 1946 and got work at Wallbergs in June. In February of the next year I started to handle salaries and personnel," Gunnar tells Max and his family. "I was young and it was somewhat "exciting" to meet all these people. We knew they had suffered a lot during the war." He inquires about what happened to Szlama and Max tells him that Szalma retired in 1965 from a job as a sales manager at a warehouse."

The excellent memories of Gunnar lead us to Paula Zuback. She was liberated from the concentration camp of Ravensbrück and came to Sweden via the "white buses" of Folke Bernadotte at the end of the Second World War. She greets us in her house in Vallås with open arms. Soon we're all sitting on the porch and listen to Paula's stories. Words in Swedish, English, German and Yiddish (Max can understand but not speak Yiddish) fills our ears. Paula remembers Szlama and Frida. She describes him "as a sweet and intelligent man" and her "as a woman who constantly fed her daughter." Max lights up. "That's my mother! Food was very special to her, probably because of her experiences in the concentration camps. She constantly fed Rachel," he explains.

Paula's son Jakub had fetched a brown colored leather bag filled with pictures in black and white. Paula is of the firm conviction that she has pictures of either Szlama or Frida or their children. Jakub produces a picture. "That´s Rachel! We've got the same picture at home!" Max exclaims. Paula tells the story while a flabbergasted Max smiles at the fact of finding an almost 50-year-old picture of his sister belonging to a perfect stranger in Sweden. The feeding was a correct statement; Rachel was a rather chubby child. The tour down memory lane ends at Furuvägen and Brogatan-Skeppargatan, the two addresses where the Fridmans once lived.

Names in ink

We're back where it all started at the parish office of St. Nikolai. Here Max studies the church records and can see for himself his, his sister Rachel and his parents' names written in ink. Seven years in Sweden condensed to a few lines in a big old book. The start of Max's life that day, his upbringing and work in New York bring him and his family back to Halmstad. "It was important for me to see the names. Many had told me about me and my parents' time here in Sweden, but this was a written proof," says Max while he smiles. "I just wished that Rachel could have been here to see it. She remembers a lot more than I do. Who knows, maybe we'll return one day."

And here, in the article above, is that same journalist, Tony Balogh, talking to me about what we had learned over the 25 years since that first visit to Sweden -- a journey that Painful Joy chronicles from the time my parents were born in the shtetls of Poland, their first families, surviving the Holocaust and how their journey continued with their second families -- until a second visit back to Halmstad. A translation of that story follows as Painful Journey explores everything before, in between -- and even afterwards.

Hallandsposten, March 21, 2022

About How Grief and Pain Are Passed on to the Next Generation by Tony Balogh

In 1998 Max Friedman visited Halmstad in order to obtain more knowledge about his parents, who survived the Holocaust. Nearly a quarter of a decade later his research has found its way into a book where he tells how much his parents' lives came to affect him. The only way to understand the present is to understand the past.

In 1968 the 20-year old American citizen Max Friedman faced the possibility of being drafted and serving in Vietnam. But there was a way out of this. "For emotional reasons," he says, "I could be given a deferment if I could prove that my parents would suffer terribly if something happened to me." Both his parents – Frieda and Szlama Friedman – had survived the Holocaust but lost their families. "My father talked to me for 20 minutes about how his wife and their two daughters hid from the Germans but were later liquidated. A beautiful but sad story," says Max, who never had to serve in Vietnam. "But the story could not have happened, not in the way my father told it," says Max, who travelled to Halmstad to find out more.

In 1998 Max Friedman worked for Bristol-Myers Squibb. That year he travelled with his family – his wife Jennifer and their sons, Noah and Eric, to Sweden. They undertook the journey just a few weeks after the passing of Max's mother. His parents had met in Sweden, got married and had two children: Max and his older sister Rachel, both born in Sweden. In mid January 1952 they left Sweden by ship for a new life in Brooklyn, New York. With his only his Swedish birth certificate Max tried to find some of his Swedish roots. I got a hold of an e-mail Max had written to the City Council. At the time I was working as a reporter for the local newspaper. For a few days I became a guide for Max and his family with visits to a lot of places and meetings with people. One meeting was with Paula Zuback who had survived the Holocaust. Not only was she able to share her memories of Frieda and Szlama, she had in her possession a picture of Rachel!

In the spring of 2022 Max is about to release his book, Painful Joy – A Holocaust Family Memoir, from Amsterdam Press in the Netherlands, a publisher who specializes in stories about the Holocaust. Thinking back on his journey to Halmstad in 1998 he finds it amazing to have met people who knew his parents and who had pictures of them as children. "The memories of my parents were exact descriptions of how they were as human beings," Max says. "They were a young couple trying to restart their lives in the light of what they had been through. I learned a lot, in fact most of it. Our parents told us hardly anything about their past. "I placed everything in the back of my mind and didn´t do any further research. That had to do with my general inability and unwillingness to deal with the experiences of the Holocaust that my parents had experienced."

During the years since then, Max started to realize how much the fate of his parents affected him and his sister. "My dad spent the rest of his life trying to forget while my mother simply couldn’t," Max says. "As soon as my mother met somebody she immediately started to speak about what she had gone through. She did this even before she said her name. She had features of schizophrenia and was paranoid. It was difficult for her and it was difficult living with her. My mother created a sort of fantasy life for herself and through her daughter, who she wanted to become the person she never could be. "This became a burden for Rachel. My sister was a diligent, quiet and a fantastic person but maybe not so social. She wasn´t fond of parties and enjoyed reading. Our mother was the exact opposite. She did not want to read and she wanted to be the center of attention. Growing up as a young girl in an Orthodox family in Europe not much was expected of her. The boys were supposed to be the breadwinners."

[Max's and Rachel's] parents had constant nightmares, probably of what we now know as PTSD. Their children had to wake them up. Their mother and father also argued a lot. About what? "Mostly about money," [Max says.] "We were quite poor. During the first nine years of my life we lived in a rather bad area of Brooklyn. My mother thought my father could have been more aggressive about pay raises – Dad worked as shipping clerk – or try to look for another job. "But my father, I think, had had such difficult experiences that he just wanted to have and maintain a quiet life with his family. He did not care much about money or worldly things. He thought of himself as being lucky. And Sweden made it possible to come to the U.S. My mother did not accept any of this. They probably were not made for each other."

But Max came to embrace his past. The journey to Sweden became the first step. In the year 2000 he started work as a freelance editorial consultant. "I was the ghostwriter for two memoirs. One of them was of the former ambassador of the USA to Sweden, the other was for the wife of the ambassador. That experience [writing about the past] spurred Max to know more about his own parents' past. "I also had grandchildren who I spoke to about my life and my parents. My parents were survivors. Had they inherited a streak of this?"

Five or six years ago Max and his family began travelling [with his family to Israel and with his grandson to Sweden] and then with his wife to Poland, Sweden and Germany. Bits and pieces were put together for a big jigsaw that could form a story.

Max´s mother had been married before the war but her first husband did not survive the Holocaust. And, Max says, "I didn´t know anything about my father´s first wife, what she looked like or the ages of their daughters. But I understood that what he had told me simply could not have happened. He did not know anything [first hand] about their fate. ["What's more,] I discovered that my father had married a woman who seemed to be a fantastic person. He spent only a few years with her, just enough to have two daughters. He could have had a fantastic life!"

Do you think it is important to any child that parents tell them something about their lives no matter what has happened? "Yes, but you have to do it at the right moment. You have to think about what you are going to say. The only way to understand the present is to understand the past. Parents are the most important persons in your life. You have to accept that you may get to know things even though some might not be so pleasant. "I´ve told you that my dad´s story could not be entirely true. You get disappointed. But we got along. He was a good man! He was [a positive influence] to live with. But I guess he must have felt guilt and shame for surviving when his wife and daughters didn´t. He probably would have wanted to be with them, even though that would have meant death. My parents were never given time to grieve." When Frieda and Szlama met in in Sweden they still had some hope of finding their families. "Somebody had told my father that his wife and children were brought to the gas chambers. But you never know. My mother was told that her husband [was last seen] in mid 1944 in Buchenwald."

Have you gotten to learn more about yourself as a human being? "Oh yeah! I learned why I sometimes suffer from panic attacks and why I have a low tolerance for stress. I learned that traumas that an adult experiences will affect the life of a child. Also my mother was severely malnourished when she came to Sweden. My sister was born a year and half later. So my sister inherited some things that were not so good such as a unusual levels of cortisol [the stress hormone] as well as bad teeth [from my mother]. I also discovered a lot more about the fantasy life of my mother. My sister and I believed everything that she told us. [Much of that turned out to not be true.]"

[Max adds,] "To understand more about your loved ones may not make your life richer but your life becomes more complete. You have a past. That past can be very complicated. Your children can get to know nothing, a little or everything. As a person you might want to tell the truth. It´s just that sometimes you do not quite know what truth looks like."